Pamela Martin, ACE

No birth date available.

Pamela Martin, ACE began working in 1991 and has twenty-six editing credits, including for Spanking the Monkey, Slums of Beverly Hills, and Ruby Sparks. Martin was nominated for an Eddie for Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris’s Little Miss Sunshine. She was also nominated for an Oscar for David O. Russell’s The Fighter. She most recently edited Battle of the Sexes, also directed by Dayton and Faris.

Pamela Martin, ACE began working in 1991 and has twenty-six editing credits, including for Spanking the Monkey, Slums of Beverly Hills, and Ruby Sparks. Martin was nominated for an Eddie for Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris’s Little Miss Sunshine. She was also nominated for an Oscar for David O. Russell’s The Fighter. She most recently edited Battle of the Sexes, also directed by Dayton and Faris.

“I’ve been using the Avid for so long that I just don’t pay as much attention to the upgrades. For me, it’s like playing the piano. It’s just a fluid extension of my body. I’ve got all my preset buttons where I like them and I don’t think about how I’m going to do it, I just do it.”

— “Pamela Martin on Cutting ‘The Fighter’: The Give and Take of Cutting Knockout Performances for Director David O. Russell.” The full text can be found in the Appendix.

“We’ve never had that great tennis movie because it’s too hard to recreate. Of course, I was worried going in, ‘How good is this going to be? Is this really going to work?’…Tennis is similar to dance. If I watch a dance movie, but I don’t see it wide, I don’t believe it. It’s a whole body sport. That’s how we’re used to watching tennis on television, and that’s what your eyes crave.”

— “‘Battle of the Sexes’ Editor Pamela Martin on Turning Emma Stone & Steve Carell Into Tennis Pros.” The full text can be found in the Appendix.

Shannon Mitchell, ACE

No birth date available.

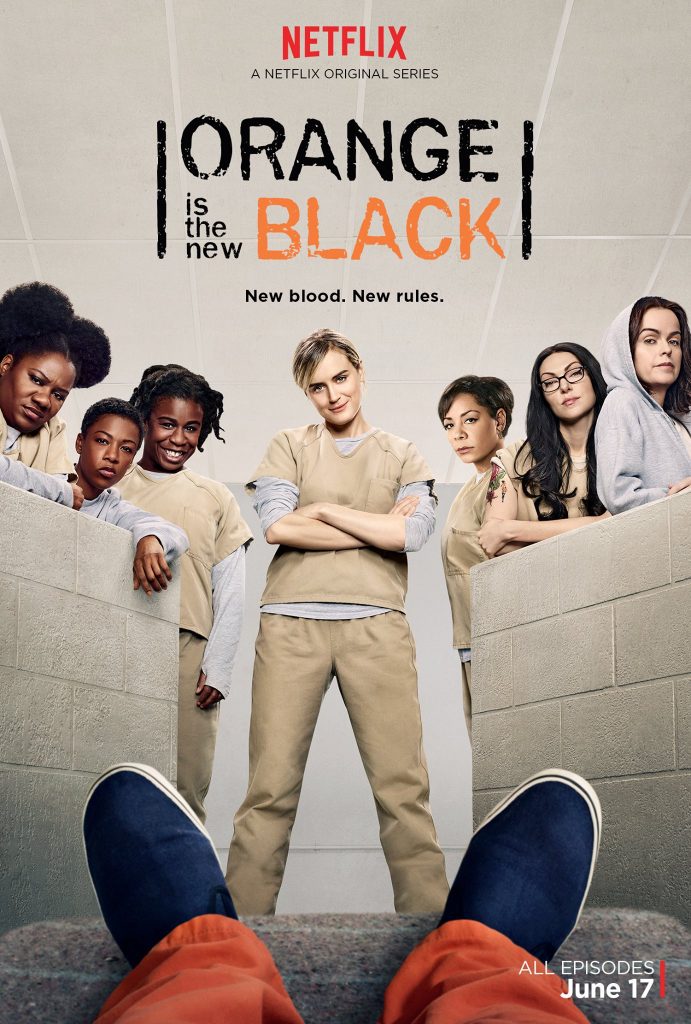

Television series have developed into a major realm of the industry, and Shannon Mitchell, ACE has worked on many of them. She started by editing feature length films in 1990 and in 2004 began editing multiple episodes of TV series, including two episodes of Expeditions to the Edge, seven episodes of Untold Stories of the ER, fourteen of United Sates of Tara, three of Shameless, thirty of Californication, and from 2013-2018, Mitchell edited twenty-three episodes of Orange Is the New Black.

Television series have developed into a major realm of the industry, and Shannon Mitchell, ACE has worked on many of them. She started by editing feature length films in 1990 and in 2004 began editing multiple episodes of TV series, including two episodes of Expeditions to the Edge, seven episodes of Untold Stories of the ER, fourteen of United Sates of Tara, three of Shameless, thirty of Californication, and from 2013-2018, Mitchell edited twenty-three episodes of Orange Is the New Black.

“I had always been fascinated by the scripting process and barely knew anything about editing at first…When I started, editing was one of the last jobs you could do without a college degree, but simply by apprenticing. That’s where I learned the craft, as an assistant, being privy to the discussions between directors and editors. Certainly there’s manual skill entailed, but it’s all about developing a sensitivity for a storyline.”

— “Bill Brownstein: The seams of the seamy side.” The full text can be found in the Appendix.

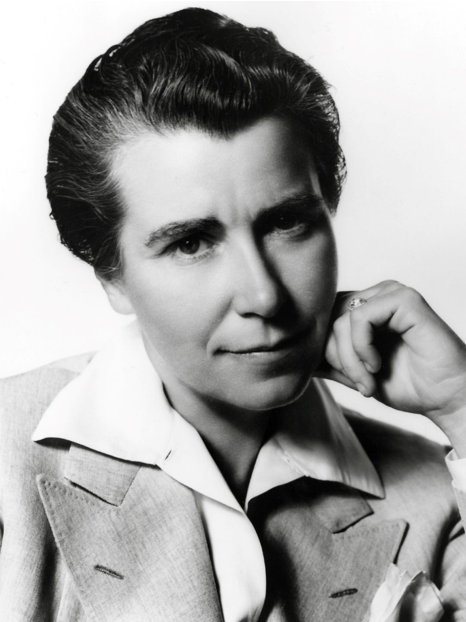

Dorothy Spencer

1909 – 2002

Dorothy Spencer entered the film industry at age fifteen. She has seventy-five feature film credits during a career of more than fifty years and was nominated four times for an Oscar. As a member of the editorial department at Fox, Spencer edited My Darling Clementine and Stagecoach (co-edited with Otho Lovering) for John Ford, Foreign Correspondent and Lifeboat for Hitchcock, To Be or Not to Be for Lubitsch, and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn for Elia Kazan, as well as many more films by those directors and others.

“When young cinema students ask me—as they often do—what it takes to become a film editor, I always tell them that patience is the first requirement. For example, there was a situation on Earthquake where we wanted to delete a scene, but I didn’t have enough material to cover the cut. [Director] Mark Ronson told me that I wouldn’t have the patience to solve the problem, but I said: ‘It’s a challenge, and I’ll lick it.’ I just insisted that there had to be a way of doing it. There’s always a way. Well, I found a way and he liked it. He just walked away shaking his head, but I thought it was fun.

Besides patience, I think you have to be dedicated to become a film editor. That’s always been more important to me than anything else. I guess my whole life has been made up of wanting to do the best I could. I enjoy editing, and I think that’s necessary, because editing is not a watching-the-clock job. I’ve been on pictures where I never even knew it was lunchtime, or time to go home. You get so involved in what you’re doing, in the challenge of creating—because I think cutting is very creative.”

“With most directors, you cut it exactly the way they want it, and there’s no room for editorial creativity. [But] Ford never told me anything and he never looked at the picture until it was finished.”

—Two excerpts from “Cutting to the Chase: Dorothy Spencer’s Action-Packed Half-Century in Hollywood” by David Meuel. The full text can be found in the Appendix.

“After a brief interlude with the advent of sound – when suddenly men became aware that it took more to a good edit than it met the eye – the studio golden age began. In those days a collaboration between director and editor was not the norm, and the director was not allowed a director’s cut – and most of the times not even into the edit room, giving the editor almost full creative reign. Dorothy Spencer worked on this environment, and edited what are today considered John Ford’s best films.”

—Excerpt from “‘A Tedious Job’ – Women and Film Editing” by Sara Galvão at Critics Associated.

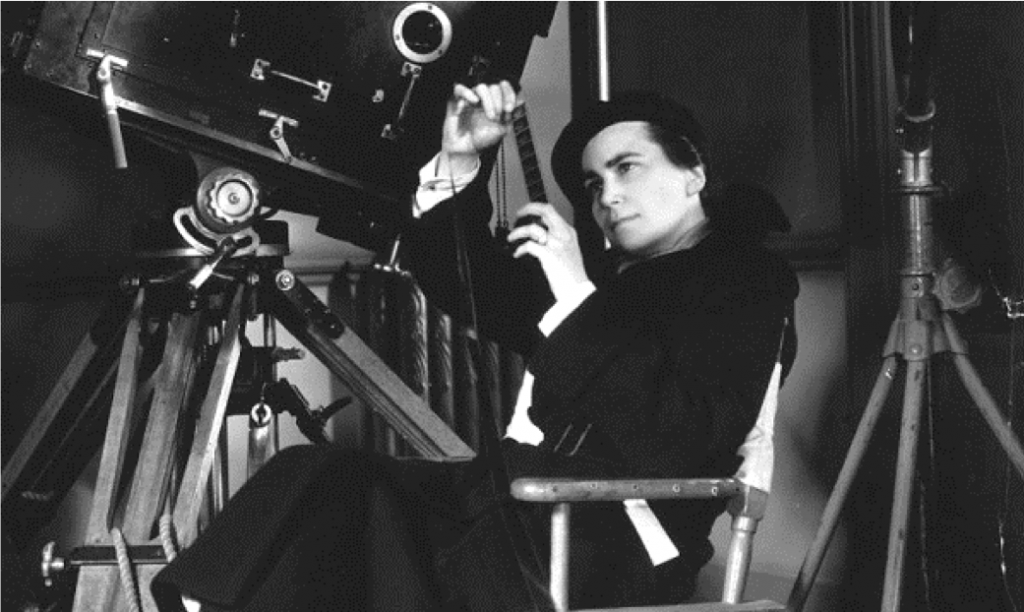

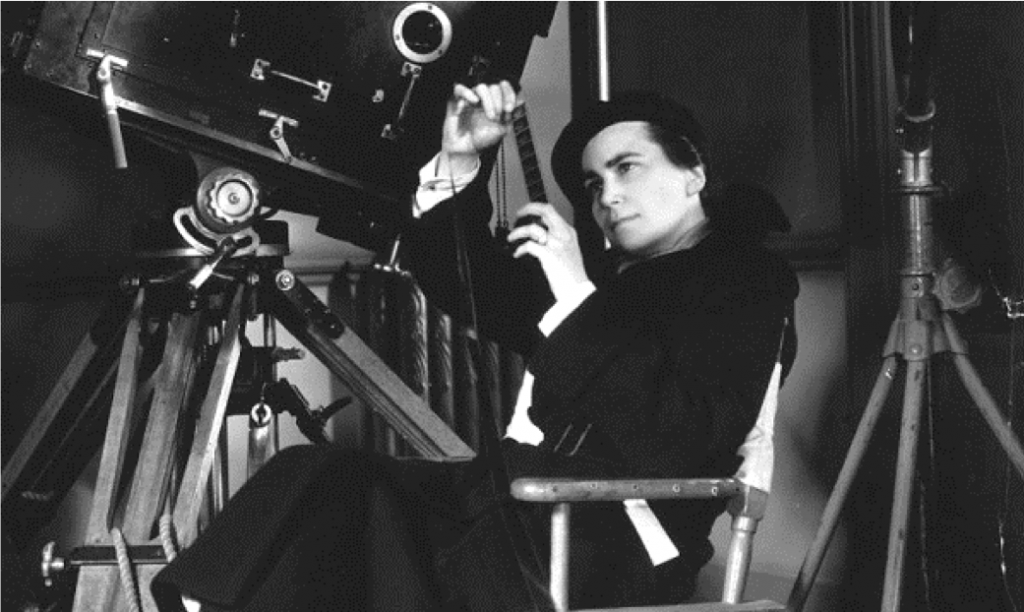

Dorothy Arzner

1897 – 1979

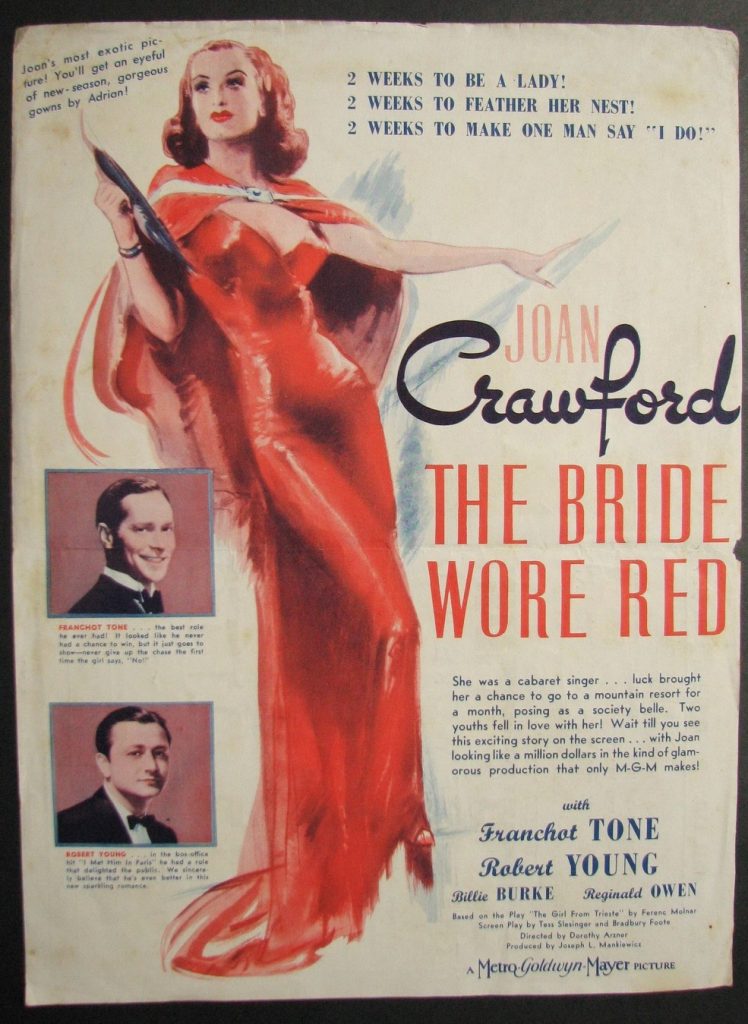

Hired as a typist at Famous Players’ Paramount Studios, Dorothy Arzner was promoted to script supervisor, writer, and “cutter” within her first six months. She worked as a film cutter from 1919-1926. From 1927-1943, as the only woman directing feature films in the Hollywood studio system, Arzner directed seventeen films, seven of which were edited by men. For the other ten, she hired Viola Lawrence for Craig’s Wife and First Comes Courage, Adrienne Fazan for The Bride Wore Red, Jane Loring for Merrily We Go To Hell, Working Girls and Anybody’s Woman, Helene Turner for Honor Among Lovers, Verna Willis for Sarah and Son, Doris Drought for Manhattan Cocktail, and Marion Morgan for Fashions for Women.

In 1938 Arzner became the first woman to join the Directors Guild of America. The DGA quotes Arzner as saying, “I was averse to having any comment made about being a woman director… because I wanted to stand up as a director and not have people make allowances that it was a woman.”

—“Sharing Our Story: Hollywood’s First Contract Director Dorothy Arzner’s ‘Dance, Girl, Dance’” by Samantha Shada. The full text can be found in the Appendix.

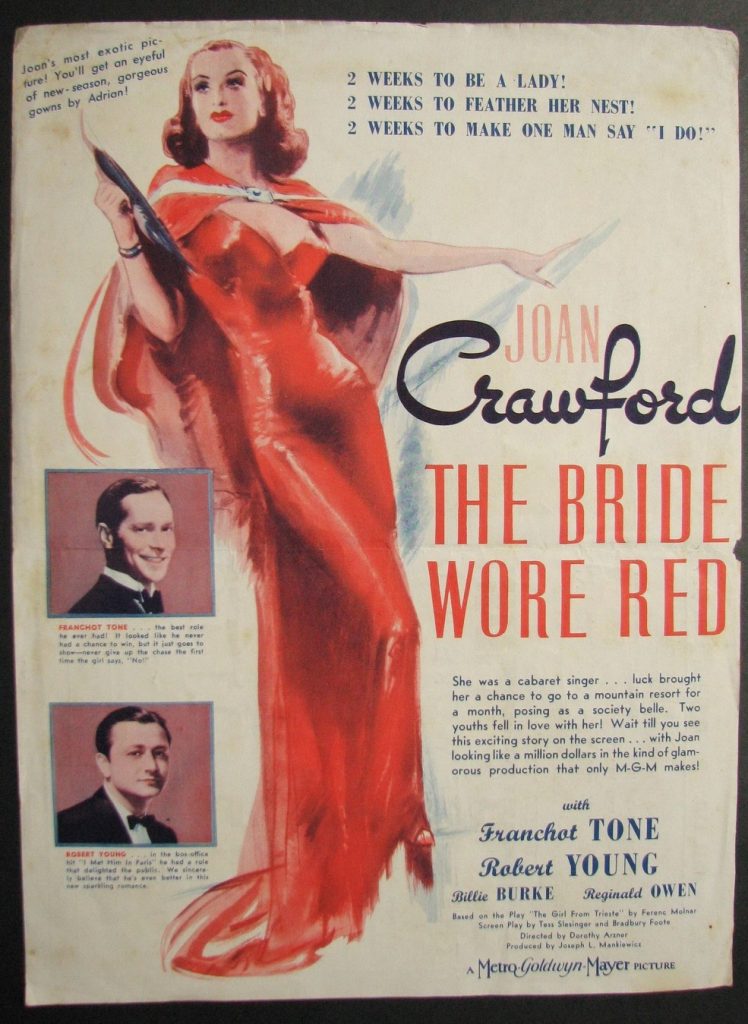

Adrienne Fazan

1906 – 1986

Adrienne Fazan began cutting films in 1931. She was helped early in her career by Dorothy Arzner, who promoted her from the short film department to feature films; she edited Arzner’s The Bride Wore Red. Fazan worked on many MGM films, including The Tell-Tale Heart, Anchors Aweigh, Singin’ in the Rain, and Lust for Life. She was nominated for an Oscar for An American in Paris and won an Oscar for Gigi. Both were directed by Vincente Minnelli, with whom she collaborated on eleven films.

“After I had sequences cut, I would show them to the director, and he would make comments. With Minnelli, he would mostly say, ‘Too tight,’ especially if it was somebody walking. He would count very slowly, ‘one, twooo, threeee, fourrrrrrr, cut!’ When I got the film on the Moviola, I would count a little faster, which, of course, was all right because I could lengthen the scenes later the way he wanted them. In the final editing, Freed would come in. Then it was up to the producer and the director to argue it out, and they would tighten the picture. Margaret Booth [MGM’s supervising editor] would yell and scream. ‘It’s too slow!’ She liked everything very tight, so I would trim it down some more.”

—“The Magic Factory: How MGM Made An American in Paris” by Donald Knox. The full text can be found in the Appendix.

“The studio made a rule that we could not work overtime without special permission…So I said, ‘Oh, the hell with you.’ I worked the overtime, but I didn’t put in for it, because I hate that business: ‘You can’t do that.’ What the hell! I’m working on the picture for the picture, trying to do as good a job as possible. Then they tell me I can’t work, I have to go home when I have work to do. I didn’t go for that.”

—“The Magic Factory: How MGM Made An American in Paris” by Donald Knox. The full text can be found in the Appendix.

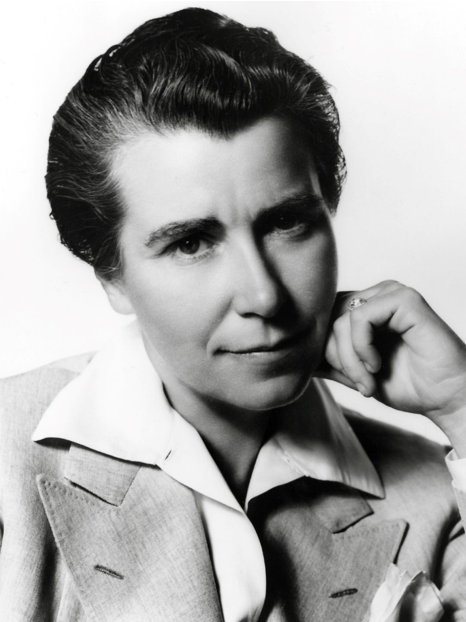

Viola Lawrence

1894 – 1973

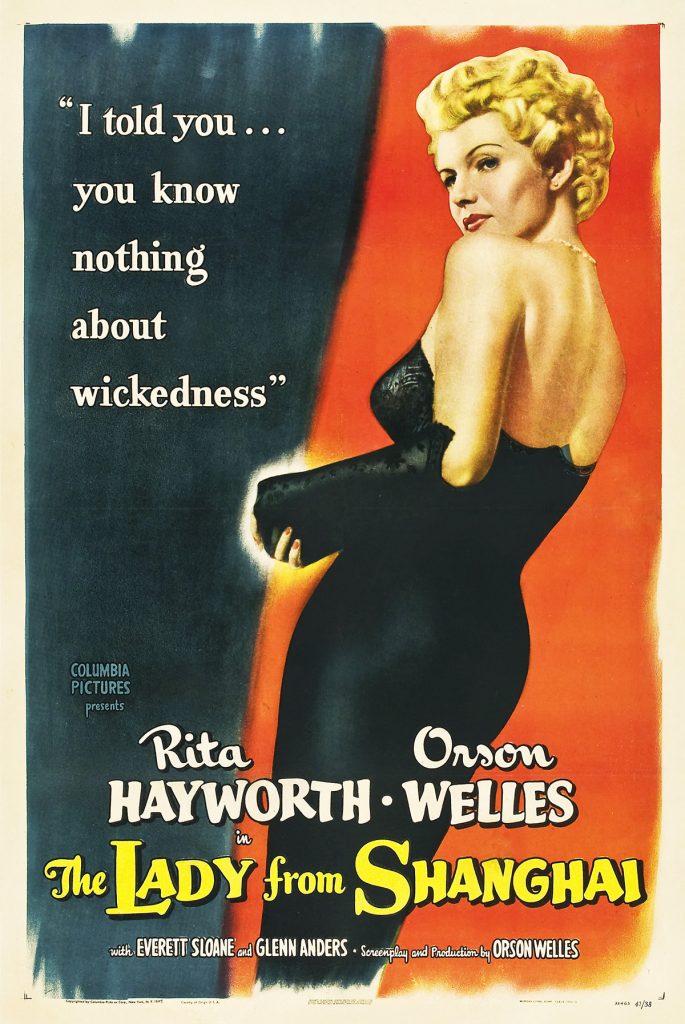

Viola Lawrence began at age eleven holding title cards for the Brooklyn-based company Vitagraph, and edited her first film in 1912. By 1915, she became the second female film cutter in cinema history (after Anna McKnight, who also worked at Vitagraph) and is considered the first female cutter in Hollywood. She moved there in 1917 and was signed by Carl Laemmle and worked variously for Universal, First National, Gloria Swanson Productions, and Columbia Pictures. She became Columbia’s supervising editor in 1925. She edited Samuel Goldwyn Studio’s first sound film, Bulldog Drummond, in 1929, then rejoined Columbia in 1934 and remained there until 1960. Lawrence edited two seminal films noir: The Lady from Shanghai and In a Lonely Place. She got two Oscar nominations, for Pepe and the musical Pal Joey. Lawrence also edited two of Dorothy Arzner’s films, Craig’s Wife and First Comes Courage.

“Quite naturally, I’m on the woman’s side in my profession. I don’t think there are enough woman cutters…If you ask me, women have more heart and feeling than men in this work. Now, listen to my masculine contemporaries yell when they hear this!”

— “The Eyes to Me Are Everything: Viola Lawrence’s 47 Years of Seeing into the Eyes of Actors to Convey the Essence of Characters” by David Meuel. The full text can be found in the Appendix.