Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE

Born 1940

Beginning in 1980 with Raging Bull, Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE has edited all of Martin Scorsese’s films. She has received seven Oscar nominations and has won three times—for Raging Bull, The Aviator, and The Departed. Schoonmaker is the second most-nominated editor in Oscar history and holds the record for the most wins. She has also won twenty-nine other awards (BAFTAs, Eddies, etc.). Schoonmaker has been a mentor and role model to many younger women editors.

Beginning in 1980 with Raging Bull, Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE has edited all of Martin Scorsese’s films. She has received seven Oscar nominations and has won three times—for Raging Bull, The Aviator, and The Departed. Schoonmaker is the second most-nominated editor in Oscar history and holds the record for the most wins. She has also won twenty-nine other awards (BAFTAs, Eddies, etc.). Schoonmaker has been a mentor and role model to many younger women editors.

Scorsese tried for years to convince Schoonmaker to work for him. She was unable to work in Hollywood, however, because she couldn’t get into the union. When Scorsese called to ask her to work on Raging Bull, she again demurred because of lack of union membership. She believes that Al Pacino got her into the union, but to this day, she doesn’t know what influence was used to gain her union membership.

Scorsese tried for years to convince Schoonmaker to work for him. She was unable to work in Hollywood, however, because she couldn’t get into the union. When Scorsese called to ask her to work on Raging Bull, she again demurred because of lack of union membership. She believes that Al Pacino got her into the union, but to this day, she doesn’t know what influence was used to gain her union membership.

“There’s a great deal of mystery in film editing, and that’s because you’re not supposed to see a lot of it. You’re supposed to feel that a film has pace and rhythm and drama, but you’re not necessarily supposed to be worried about how that was accomplished. And because there is so little understanding of what really great editing is, a film that’s flashy, has a lot of quick cuts and explosions, gets particular attention. For example, with The Aviator, which I won an Oscar for—I’m sure that decision was based largely on the very elaborate plane crash that Howard Hughes had. That’s so dramatic, and you can really see the editing there, but for me, and for a lot of editors and directors, the more interesting editing is not so visible. It’s the decisions that go into building a character, a performance, for example, or how you rearrange scenes in a movie, if it’s not working properly, so that you can get a better dramatic build.”

“The priority is absolutely on the best take for performance, and frankly I don’t understand why people get so hung up on these issues, because if you look at films throughout history, you will see enormous continuity errors everywhere, particularly when you’re talking about the Academy aspect ratio where you see more in the frame. Even in The Red Shoes, a film that nobody ever has complaints about, there are enormous continuity bumps, and it doesn’t matter. You know why? Because you’re being carried along by the power of the film. So throughout our history of improvisational cutting, we have decided to go with the performance, or in this case particularly with the humor of a line, as opposed to trying to make sure a coffee cup is in the right place.”

— Two excerpts from “Interview: Thelma Schoonmaker” by Nick Pinkerton. The full interview can be found in the Appendix.

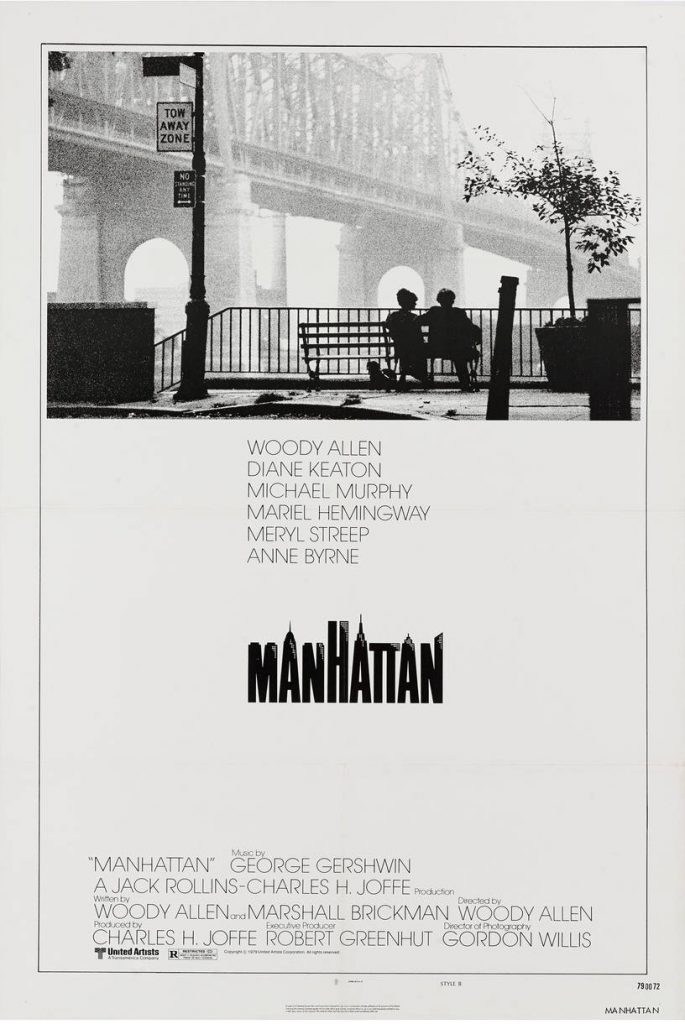

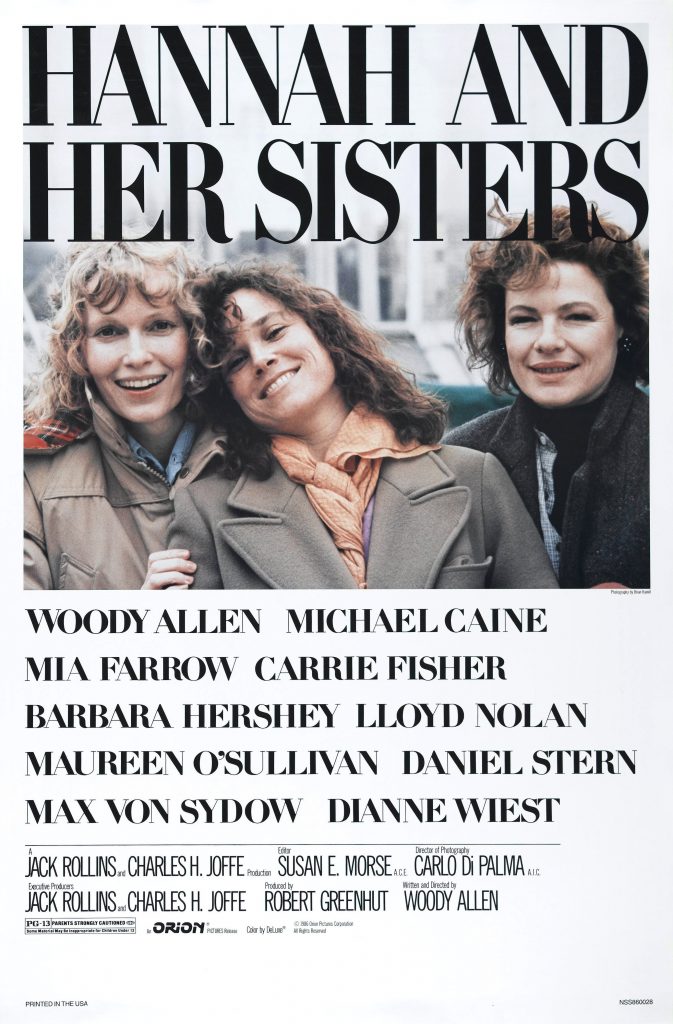

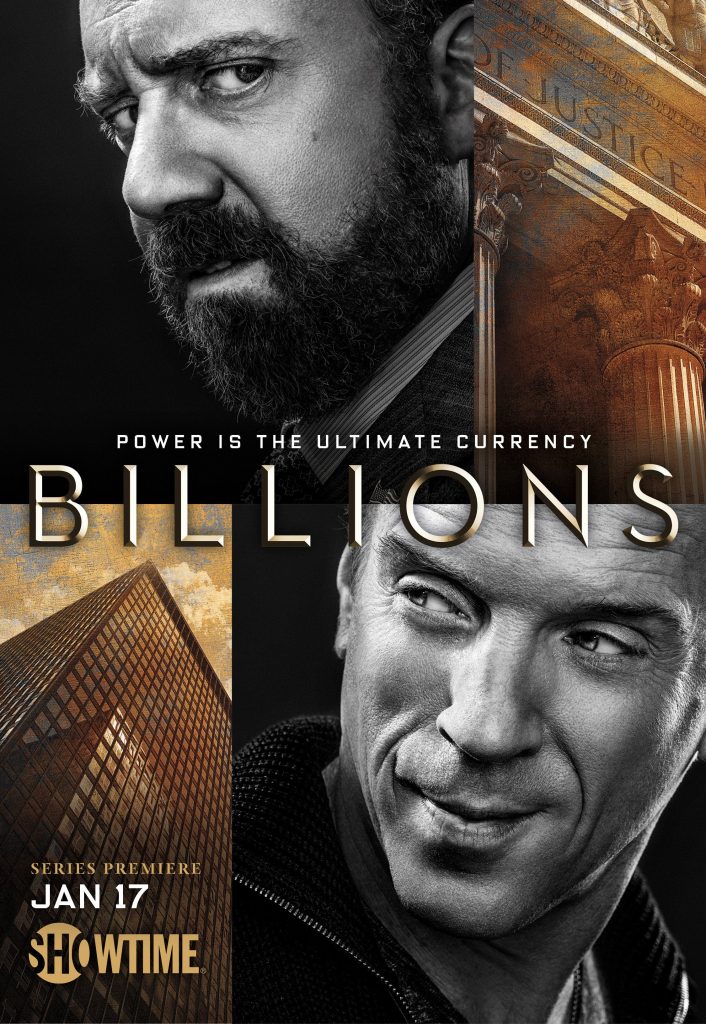

Susan Morse, ACE was Woody Allen’s primary editor from 1977-1998, during which time she edited twenty-two of his films, from Manhattan to Celebrity. She got an Oscar nomination for Hannah and Her Sisters, and five BAFTA nominations for various films by Allen. Morse has forty-one credits, and in the 2010s, she edited the third season of Louie and three episodes of Billions.

Susan Morse, ACE was Woody Allen’s primary editor from 1977-1998, during which time she edited twenty-two of his films, from Manhattan to Celebrity. She got an Oscar nomination for Hannah and Her Sisters, and five BAFTA nominations for various films by Allen. Morse has forty-one credits, and in the 2010s, she edited the third season of Louie and three episodes of Billions.

Beginning in 1980 with Raging Bull, Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE has edited all of Martin Scorsese’s films. She has received seven Oscar nominations and has won three times—for Raging Bull, The Aviator, and The Departed. Schoonmaker is the second most-nominated editor in Oscar history and holds the record for the most wins. She has also won twenty-nine other awards (BAFTAs, Eddies, etc.). Schoonmaker has been a mentor and role model to many younger women editors.

Beginning in 1980 with Raging Bull, Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE has edited all of Martin Scorsese’s films. She has received seven Oscar nominations and has won three times—for Raging Bull, The Aviator, and The Departed. Schoonmaker is the second most-nominated editor in Oscar history and holds the record for the most wins. She has also won twenty-nine other awards (BAFTAs, Eddies, etc.). Schoonmaker has been a mentor and role model to many younger women editors. Scorsese tried for years to convince Schoonmaker to work for him. She was unable to work in Hollywood, however, because she couldn’t get into the union. When Scorsese called to ask her to work on Raging Bull, she again demurred because of lack of union membership. She believes that Al Pacino got her into the union, but to this day, she doesn’t know what influence was used to gain her union membership.

Scorsese tried for years to convince Schoonmaker to work for him. She was unable to work in Hollywood, however, because she couldn’t get into the union. When Scorsese called to ask her to work on Raging Bull, she again demurred because of lack of union membership. She believes that Al Pacino got her into the union, but to this day, she doesn’t know what influence was used to gain her union membership.