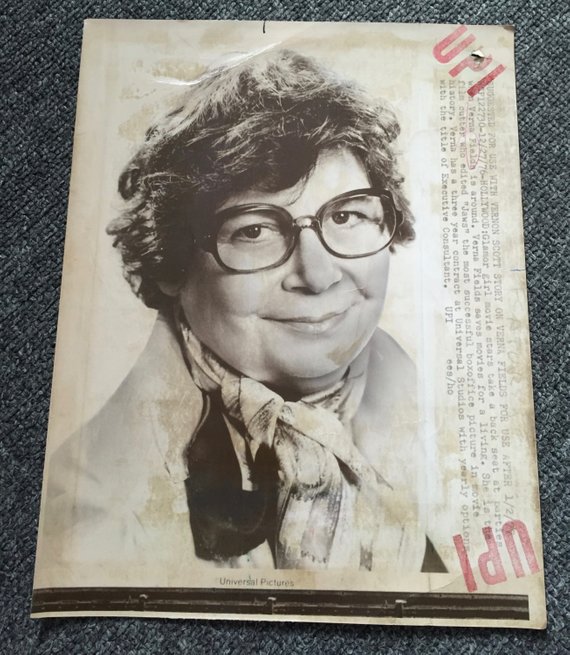

Carol Littleton, ACE

Born 1942

Carol Littleton, ACE has thirty-eight credits and was nominated for an Oscar for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. She had a long collaboration with Lawrence Kasdan, editing eight of his ten films, including The Big Chill, Body Heat, and The Accidental Tourist. She also edited four films for Jonathan Demme, including Swimming to Cambodia, The Manchurian Candidate, and Beloved. Littleton won an Emmy for Tuesdays with Morrie, and in 2016 she received a Career Achievement Award from ACE.

Carol Littleton, ACE has thirty-eight credits and was nominated for an Oscar for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. She had a long collaboration with Lawrence Kasdan, editing eight of his ten films, including The Big Chill, Body Heat, and The Accidental Tourist. She also edited four films for Jonathan Demme, including Swimming to Cambodia, The Manchurian Candidate, and Beloved. Littleton won an Emmy for Tuesdays with Morrie, and in 2016 she received a Career Achievement Award from ACE.

“…the most important thing is learning how to analyze a story. What are the elements that make a story achieve its full potential? As an editor I analyze the story, and figure out how to make it as rich as possible, to have the most emotional impact. The main task of the editor is to compress screen time while being aware of an accretion of detail in the actors’ performances to guide the story toward its maximum emotional effect. Our work is interpretive, and the more analytical tools we have, the more successful we are.”

—“An Interview with Carol Littleton ACE” by Janet Dalton. The full interview can be found in the Appendix.

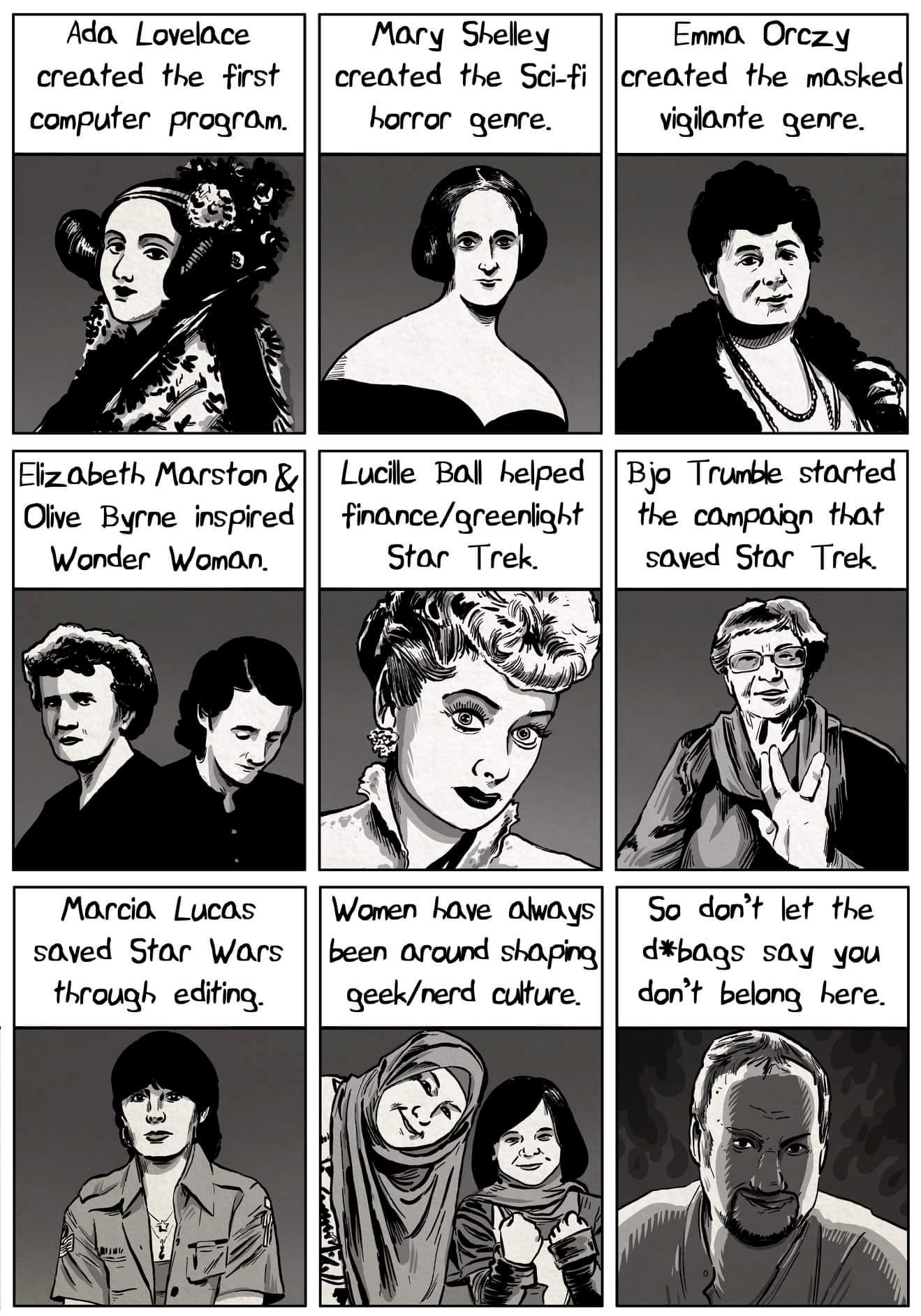

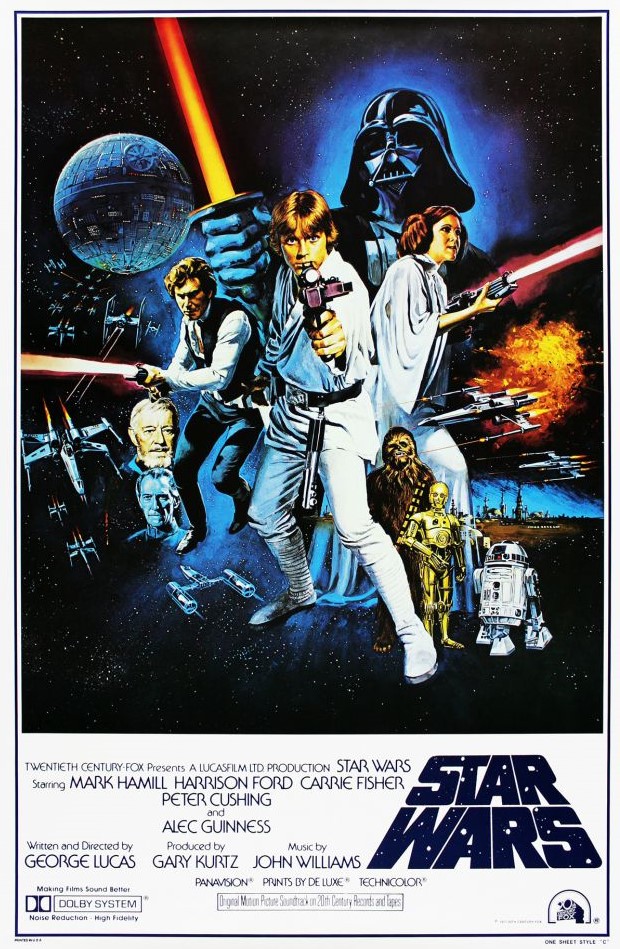

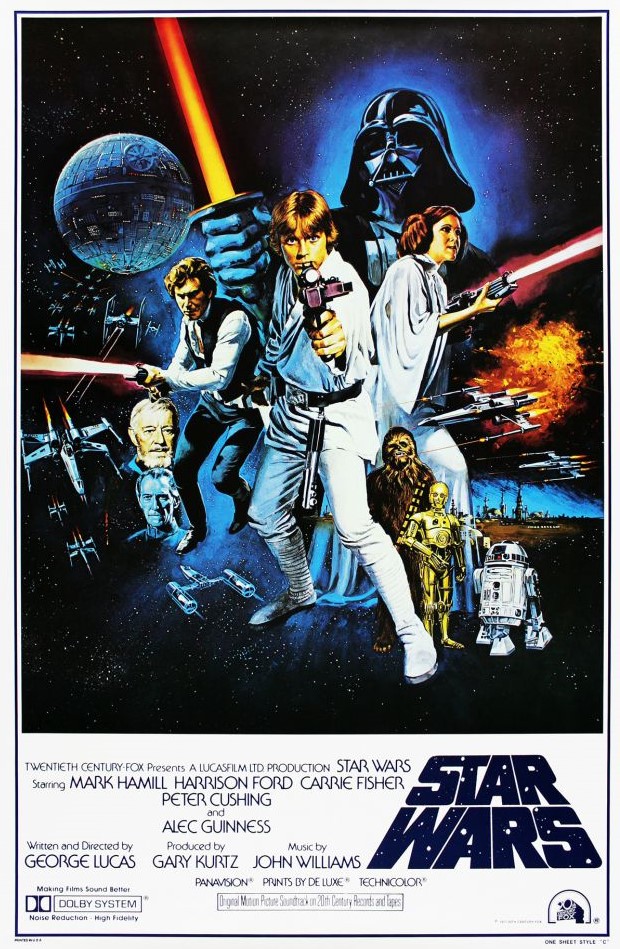

Marcia Lucas

Born 1945

Marcia Lucas edited Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and was then the supervising editor of his next two films, Taxi Driver and New York, New York. The first film by her husband George Lucas that she co-edited (with Verna Fields) was American Graffiti. She then co-edited the first Star Wars: Episode IV with Paul Hirsch and Richard Chew. They won an Oscar and a Saturn Award. Lucas co-edited the next two Star Wars: Episodes V and VI. After their divorce, she retired from editing work. But later, in the same galaxy…

“I love editing and I’m real gifted at it,” she stated in 1983. “I have an innate ability to take good material and make it better, or take bad material and make it fair. I’m compulsive about it. I think I’m even an editor in real life.”

“I felt we were partners, partners in the ranch, partners in our home, and we did these films together. I wasn’t a fifty percent partner, but I felt I had something to bring to the table. I was the more emotional person who came from the heart, and George was the more intellectual and visual, and I thought that provided a nice balance. But George would never acknowledge that to me. I think he resented my criticisms, felt that all I ever did was put him down. In his mind, I always stayed the stupid Valley girl. He never felt I had any talent, he never felt I was very smart and he never gave me much credit. When we were finishing Jedi, George told me he thought I was a pretty good editor. In the sixteen years of our being together I think that was the only time he complimented me.”

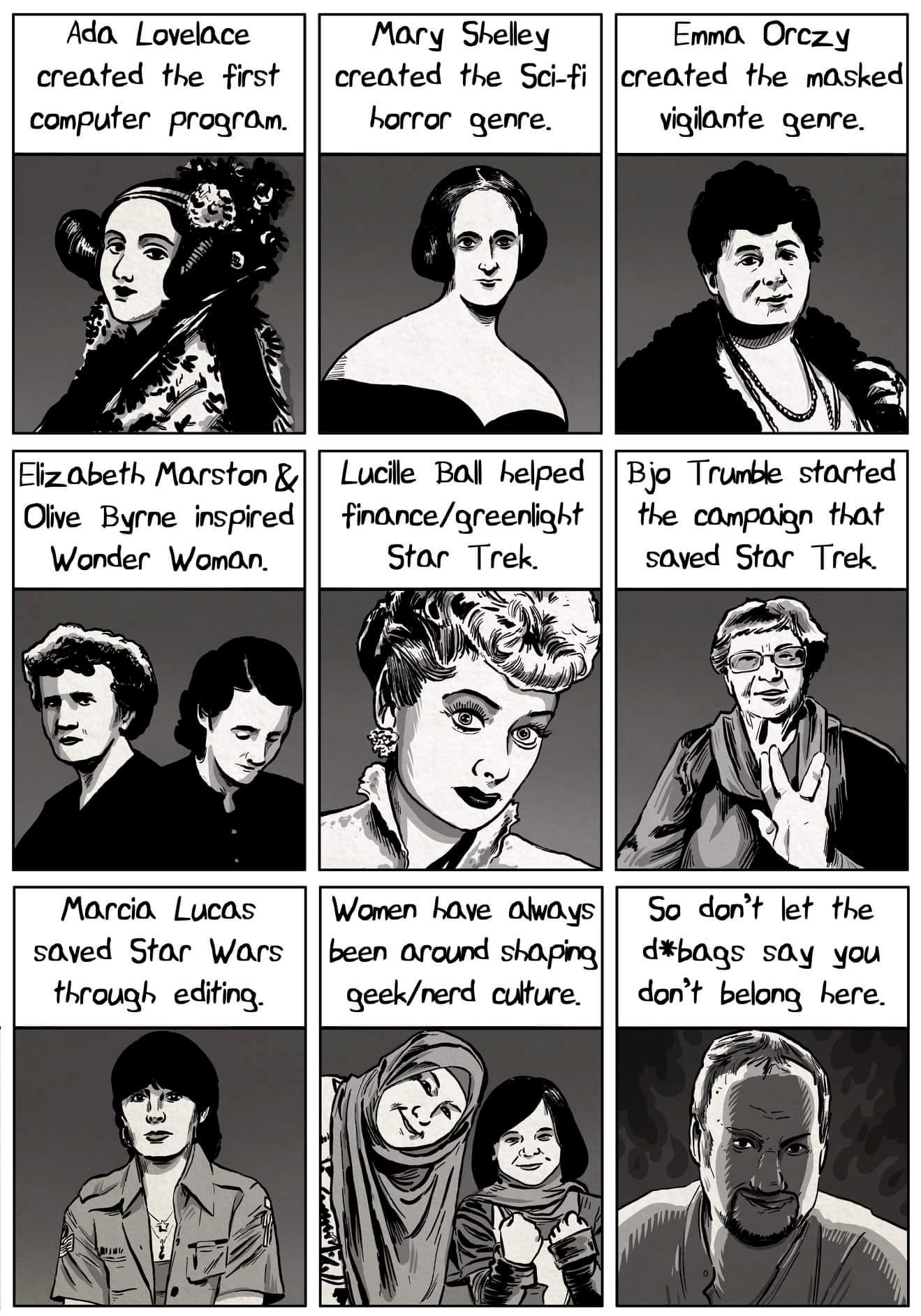

(I love this cartoon but sorry, I couldn’t track down who did it.)

About editing Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore:

“Marty [Scorsese] called, and asked if I would do his first studio feature. He was terrified of the studio executives, that Warners was going to give him some old fuddy-duddy editor or a spy–the studios were known for having spies on such projects. Marty liked to edit, and I felt like I was being hired to cut a movie so I wouldn’t cut it, so I’d let the director cut it. But I thought, if I’m ever going to get any real credit, I’m going to have to cut a movie for somebody besides George. ‘Cause if I’m cutting for my husband, they’re going to think, George lets his wife play around in the cutting room. George agreed with that.”

— Three excerpts from “In Tribute to Marcia Lucas” by Michael Kaminski. The full text can be found in the Appendix

Cut to:

The Match Cut

It is the editor, as much as or more than anyone, who wields rigorous control over the passage of onscreen time, making thousands of decisions that accord a picture its pace and rhythm.

One of the most celebrated editing moments in world cinema, critics agree, occurs in Lawrence of Arabia. It involves an onscreen juxtaposition of the kind known as a match cut, where the cutting highlights affinities between two successive images.

In one scene, Lawrence is ordered to the Arabian Peninsula. Receiving the order, he leans over to light the cigarette of a British diplomat, then stares transfixed at the still-lighted match between his fingers. Lawrence blows out the match, and in the instant he does, the action cuts from the smoldering flame to a panorama of the sunrise over burning desert sands.

In one scene, Lawrence is ordered to the Arabian Peninsula. Receiving the order, he leans over to light the cigarette of a British diplomat, then stares transfixed at the still-lighted match between his fingers. Lawrence blows out the match, and in the instant he does, the action cuts from the smoldering flame to a panorama of the sunrise over burning desert sands.

In that single cut — born when Ms. Coates chose to splice two discrete bits of film together — is contained the passage of time, a journey through space and a delicious visual pun: a literal “match” cut. Steven Spielberg has described that cut as “the transition that blew me away” when he first saw the film as a youth.

–Margalit Fox, The New York Times, May 9, 2018

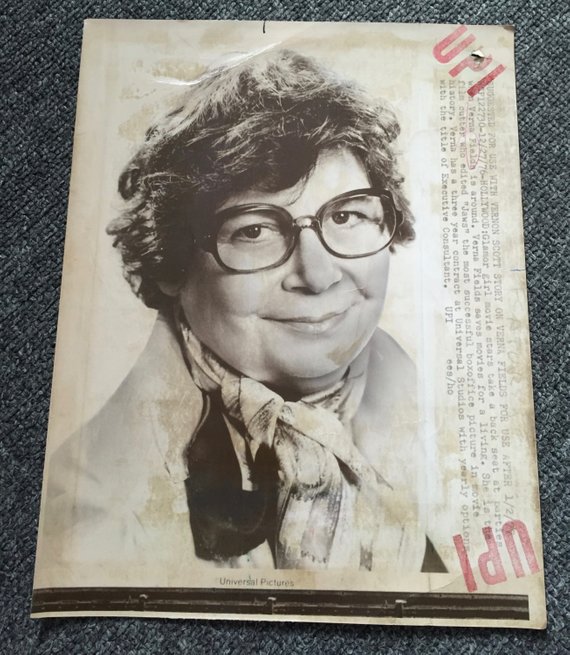

Verna Fields

1918 – 1982

Verna Fields began as a sound editor in 1956 and continued that work even after becoming a film editor; she has nineteen sound editing credits as well as nineteen for film editing. Irving Lerner’s Studs Lonigan was the first, in 1960, and later she edited Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool. By 1972 Fields was working closely with three directors early in their careers: Peter Bogdanovich, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg. She became known as their “mother cutter.” The success of Bogdanovich’s What’s Up, Doc? and Paper Moon, Lucas’ American Graffiti (with Marcia Lucas as a co-editor) and Spielberg’s Jaws brought her a level of recognition that was unique among film editors at the time. She received both an Oscar and an Eddie Award for Jaws. Within a year of the film’s release, in 1976, Fields was appointed Vice-President for Feature Production at Universal Studios, making her one of the first women to enter upper-level management in the entertainment industry. Her career as an executive at Universal lasted for only six years, cut short by her death in 1982 at age sixty-four.

“I was the liaison with the studio for Steven [Spielberg]. When they thought of ditching the picture because the shark wasn’t working, I told them, ‘Keep doing it, even if you need to use miniatures.’” Fields became an overnight success after winning the Oscar. “Steven told me it was because I had cut the first picture that was a monumental success in which you can really see the editing. And people discovered that it was a woman who edited Jaws.”

—”Verna Fields” by Gerald Peary. The full interview can be found in the Appendix.

Carol Littleton, ACE has thirty-eight credits and was nominated for an Oscar for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. She had a long collaboration with Lawrence Kasdan, editing eight of his ten films, including The Big Chill, Body Heat, and The Accidental Tourist. She also edited four films for Jonathan Demme, including Swimming to Cambodia, The Manchurian Candidate, and Beloved. Littleton won an Emmy for Tuesdays with Morrie, and in 2016 she received a Career Achievement Award from ACE.

Carol Littleton, ACE has thirty-eight credits and was nominated for an Oscar for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. She had a long collaboration with Lawrence Kasdan, editing eight of his ten films, including The Big Chill, Body Heat, and The Accidental Tourist. She also edited four films for Jonathan Demme, including Swimming to Cambodia, The Manchurian Candidate, and Beloved. Littleton won an Emmy for Tuesdays with Morrie, and in 2016 she received a Career Achievement Award from ACE.

In one scene, Lawrence is ordered to the Arabian Peninsula. Receiving the order, he leans over to light the cigarette of a British diplomat, then stares transfixed at the still-lighted match between his fingers. Lawrence blows out the match, and in the instant he does, the action cuts from the smoldering flame to a panorama of the sunrise over burning desert sands.

In one scene, Lawrence is ordered to the Arabian Peninsula. Receiving the order, he leans over to light the cigarette of a British diplomat, then stares transfixed at the still-lighted match between his fingers. Lawrence blows out the match, and in the instant he does, the action cuts from the smoldering flame to a panorama of the sunrise over burning desert sands.