Lyudmila Feiginova

Dates unknown; deceased.

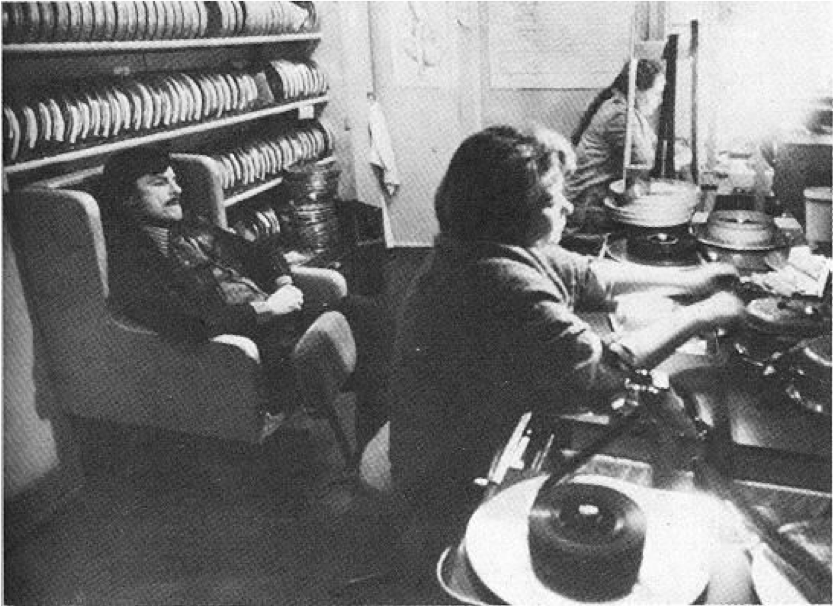

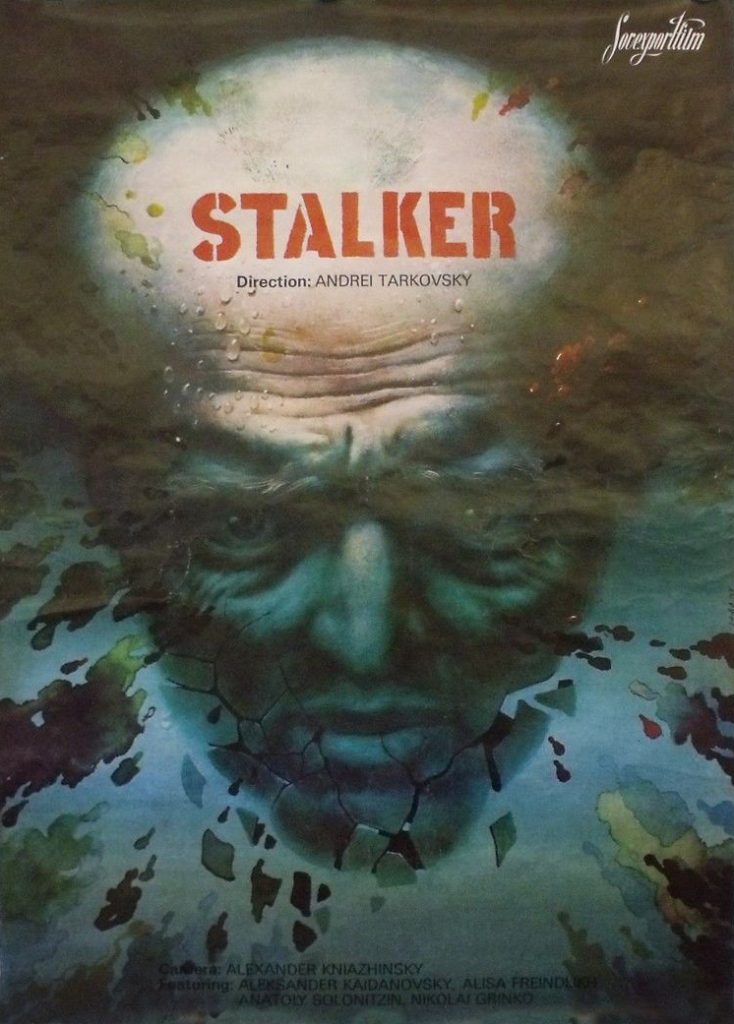

Lyudmila Feiginova (also sometimes credited as Feyginova) started working as an editor in 1959. She edited most of Andrei Tarkovsky’s films, including Stalker, The Mirror, Solaris, and Andrei Rublev, and numerous other films by other directors. She was also assistant editor, though uncredited, on Dersu Uzala, Akira Kurosawa’s film set in Russia.

“Feiginova was a highly professional — and very interesting — person. While working on the films of Tarkovski she would often suggest significant changes during the editing of the film. For example, in Mirror, Feiginova was the one who proposed that the scene with the stutterer should open the film. That scene was based on a memory Andrei had from the house of his mother; it was something he had watched on TV. The scene was originally intended for the middle of the film, but Feiginova suggested that it should be the opening scene of Mirror — and Andrei agreed.

Another scene which Feignova rearranged was that of the monologue of Stalker’s wife. This scene takes place in the bar, and its intended place in the film was just after the chat of the three protagonists, before taking off for the Zone. Feiginova however suggested that it would be more interesting if the scene appeared at the very end, after Stalker’s return. To Andrei this did not seem appropriate at first, since the scene had been shot in the bar, with interiors different from those of Stalker’s house. Feiginova responded, “Nobody will notice that it was shot elsewhere, because they will all be intently concentrating on the actress,” and true enough: Nobody notices this little detail unless it is pointed out to them, as Alissa Freindlikh’s performance is so utterly captivating.”

—Comment by Tarkovskaia in “An Interview with Marina Tarkovskaia and Alexander Gordon”. The full interview can be found in the appendix.

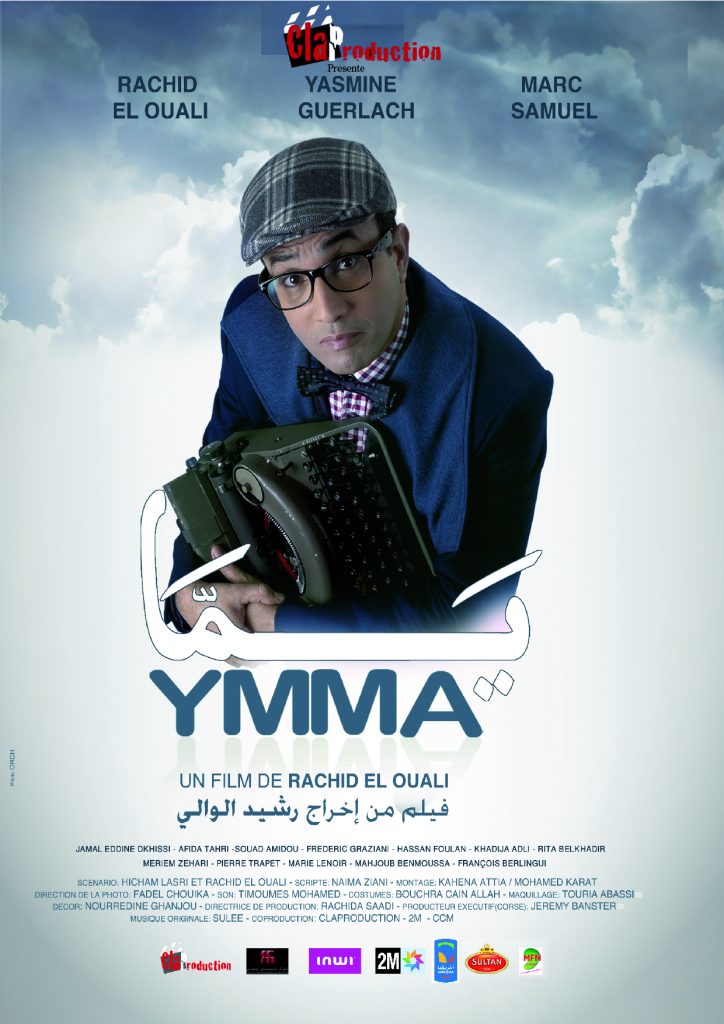

Kahéna Attia (sometimes also credited as Attia-Reveill) is a Tunisian editor who began her career as an assistant editor in 1971 and has twenty-five credits. Her first is for Ousmane Sembene’s Camp de Thiaroye; she also edited his Faat-Kine. Attia won best editing awards at the National Film Festival of Tangier for Rachid El Ouali’s Ymma and at FESPACO for Nadia Fares’ Honey and Ashes. She also edited Mohamed Challouf’s Tahar Cherera—In the Shadow of the Baobab, a documentary about the father of pan-cinematic Pan-Africanism and founder in 1966 of Carthage Film Days, the first film festival in Africa and the Arab World.

Kahéna Attia (sometimes also credited as Attia-Reveill) is a Tunisian editor who began her career as an assistant editor in 1971 and has twenty-five credits. Her first is for Ousmane Sembene’s Camp de Thiaroye; she also edited his Faat-Kine. Attia won best editing awards at the National Film Festival of Tangier for Rachid El Ouali’s Ymma and at FESPACO for Nadia Fares’ Honey and Ashes. She also edited Mohamed Challouf’s Tahar Cherera—In the Shadow of the Baobab, a documentary about the father of pan-cinematic Pan-Africanism and founder in 1966 of Carthage Film Days, the first film festival in Africa and the Arab World.

“Americans say that the writer is the first editor, and the editor is the last writer. This is an apt formulation. You have to intentionally (re)organize the images to extract their essence, to expose the meaning. That’s where everything gets complicated: if a word betrays you, you can always replace it. But an image is fixed on the film reel, it is irreplaceable. One must then manipulate it, weave it, cut it, rethink it, etc.”

“Americans say that the writer is the first editor, and the editor is the last writer. This is an apt formulation. You have to intentionally (re)organize the images to extract their essence, to expose the meaning. That’s where everything gets complicated: if a word betrays you, you can always replace it. But an image is fixed on the film reel, it is irreplaceable. One must then manipulate it, weave it, cut it, rethink it, etc.”