Barbara “Bobbie” McLean

1903 – 1996

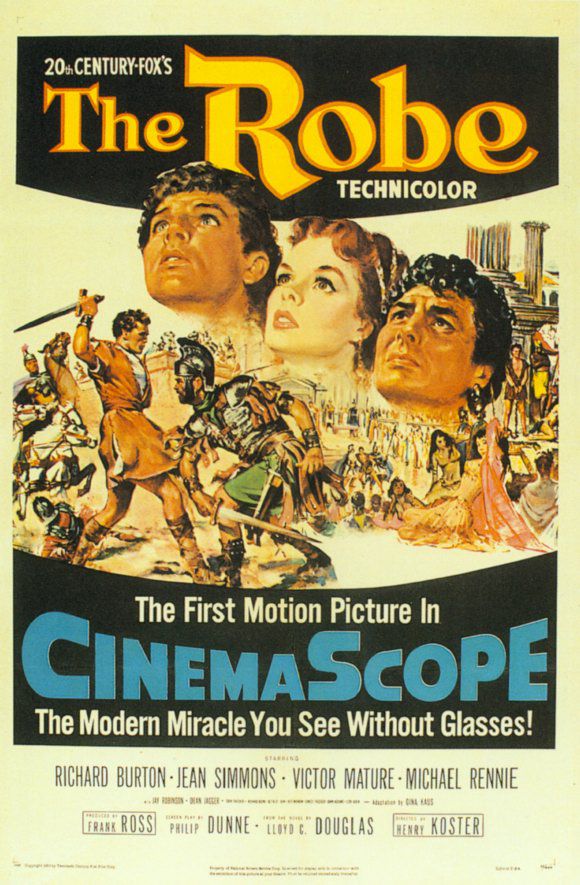

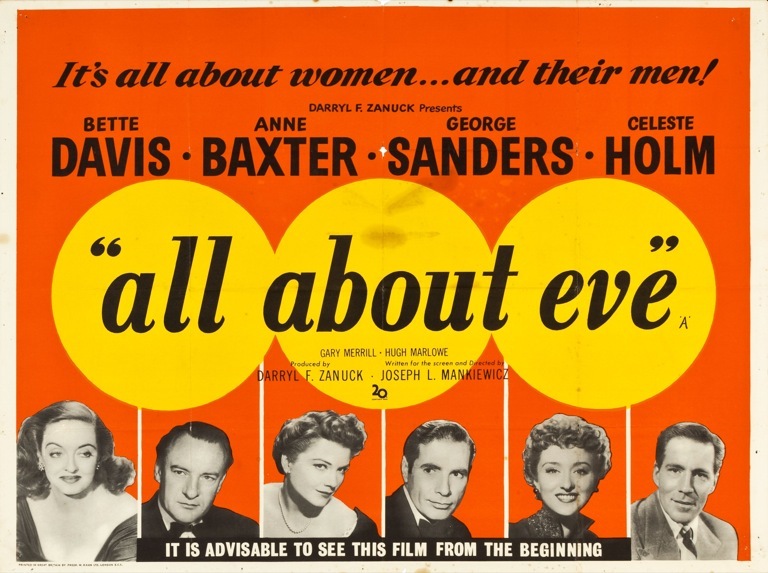

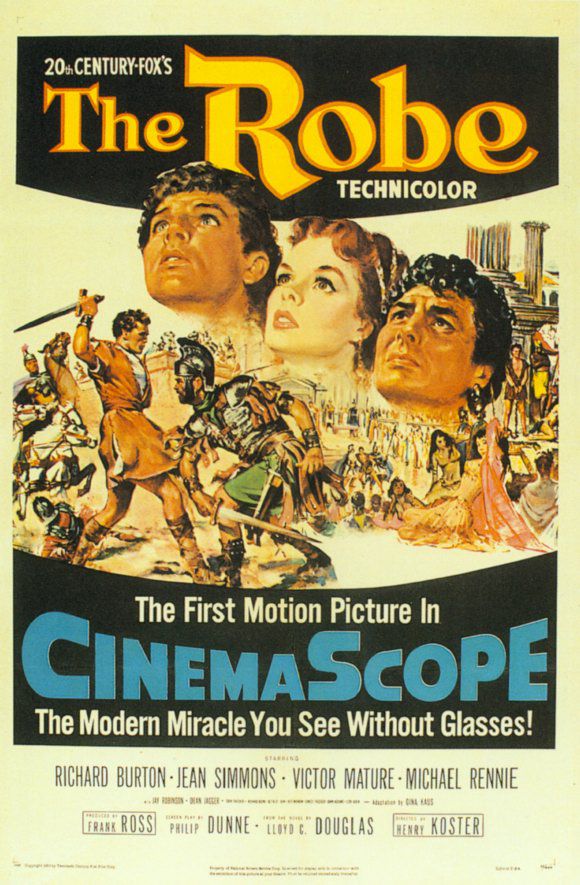

Barbara “Bobbie” McLean has sixty-two film credits. From the 1930s through 1960s, she was 20th Century Fox’s most conspicuous editor and went on to be the head of the editing department and was known in trade publication columns as “Hollywood’s Editor-in-Chief.” McLean received more Academy Award nominations than any other editor during her lifetime (for Les Misérables, Lloyd’s of London, Alexander’s Ragtime Band, The Rains Came, Song of Bernadette, Wilson, and All About Eve). She won the Oscar for Wilson in 1945. Her total of seven nominations was not surpassed until 2012 by Michael Kahn. She also edited Fox’s first venture into Cinemascope, The Robe. Among many other honors, McLean received a Career Achievement Award from ACE. In the obituary published in The Independent, Adrian Dannatt described McLean as “a revered editor who perhaps single-handedly established women as vital creative figures in an otherwise patriarchal industry.”

“I could get to every department and do everything, even to do a good deal of working on music…You’d go on the scoring stage when they’d do the music, to see what he would be doing. You were there watching out for your own good. You know, to know how everything was going to fit. Each thing you learned a little more.”

“Sometime later, McNeil [another editor] had her accompany him to the projection room while Zanuck viewed the rushes with the editor. McNeil was supposed to take note of Zanuck’s comments and discuss things with him, but he never wrote anything down and, as McLean stated, “would forget it or something.” When Zanuck complained, “Why don’t you do what I told you to do?” McNeil tried blaming McLean for not making a note of it. McLean, tired of being ignored and pushed to the other side of the room behind a tiny desk, was livid. “Now look, Alan, don’t you pass the buck to me,” she shot back across the room. “I can’t hear what Mr. Zanuck tells you. Now, if you can’t remember it, don’t you blame it on me.” As McLean recalled tartly, “From there on, Zanuck would yell the notes out so I could hear them. I suppose that’s how he finally discovered that if I could hear, then we would do the changes.” McLean’s grit won her the right to cut the well-named Gallant Lady herself—the first time she received sole credit. Bobbie, a fine sailor in her rare moments away from the editing room, celebrated by christening her new craft Gallant Lady.”

“McLean’s summary of editing was essentially ‘making filmed matters seem better than they are.’ So much for the auteur theory.”

— Three excerpts from “Barbara McLean: Editing, Authorship, and the Equal Right to Be the Best” by J. E. Smyth. The full text can be found in the Appendix.

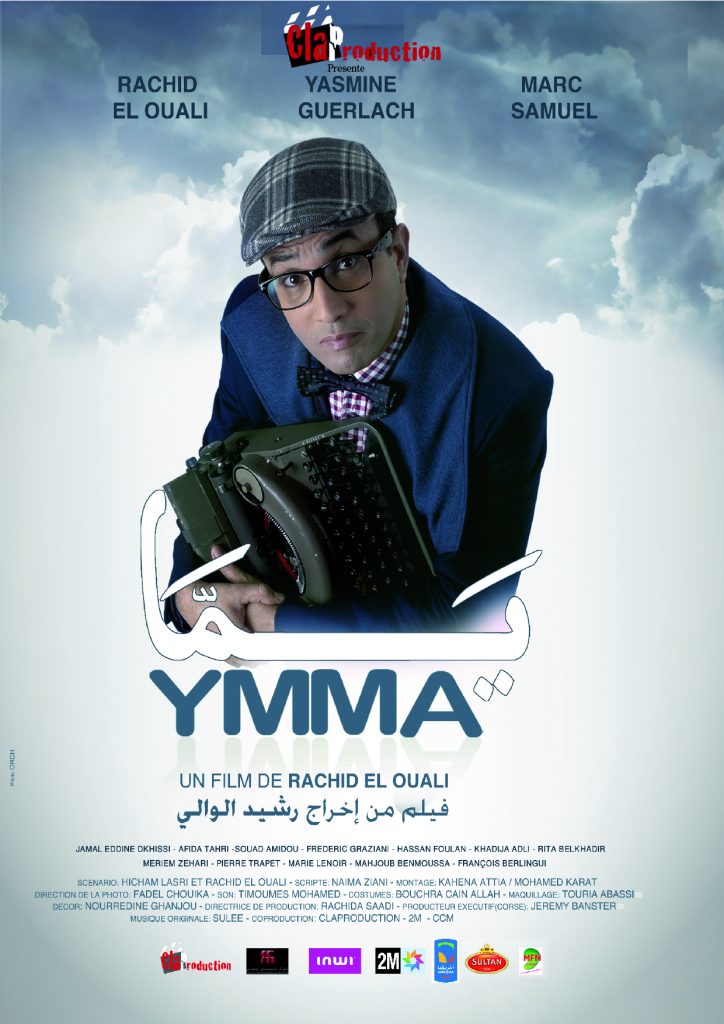

Kahéna Attia (sometimes also credited as Attia-Reveill) is a Tunisian editor who began her career as an assistant editor in 1971 and has twenty-five credits. Her first is for Ousmane Sembene’s Camp de Thiaroye; she also edited his Faat-Kine. Attia won best editing awards at the National Film Festival of Tangier for Rachid El Ouali’s Ymma and at FESPACO for Nadia Fares’ Honey and Ashes. She also edited Mohamed Challouf’s Tahar Cherera—In the Shadow of the Baobab, a documentary about the father of pan-cinematic Pan-Africanism and founder in 1966 of Carthage Film Days, the first film festival in Africa and the Arab World.

Kahéna Attia (sometimes also credited as Attia-Reveill) is a Tunisian editor who began her career as an assistant editor in 1971 and has twenty-five credits. Her first is for Ousmane Sembene’s Camp de Thiaroye; she also edited his Faat-Kine. Attia won best editing awards at the National Film Festival of Tangier for Rachid El Ouali’s Ymma and at FESPACO for Nadia Fares’ Honey and Ashes. She also edited Mohamed Challouf’s Tahar Cherera—In the Shadow of the Baobab, a documentary about the father of pan-cinematic Pan-Africanism and founder in 1966 of Carthage Film Days, the first film festival in Africa and the Arab World.