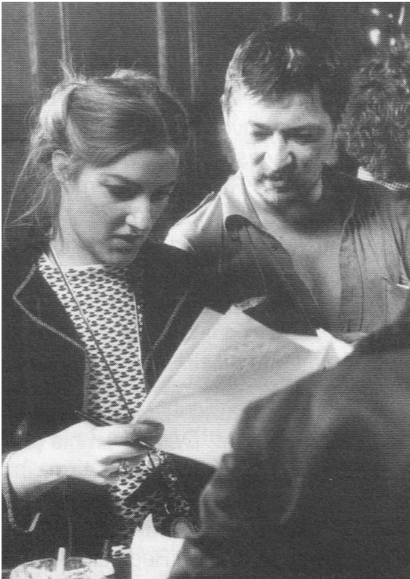

Juliane Lorenz

Born 1957

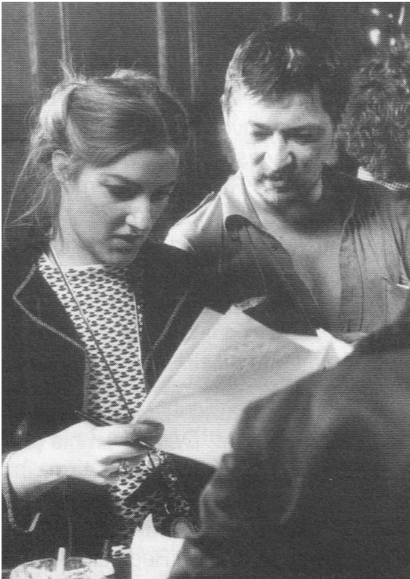

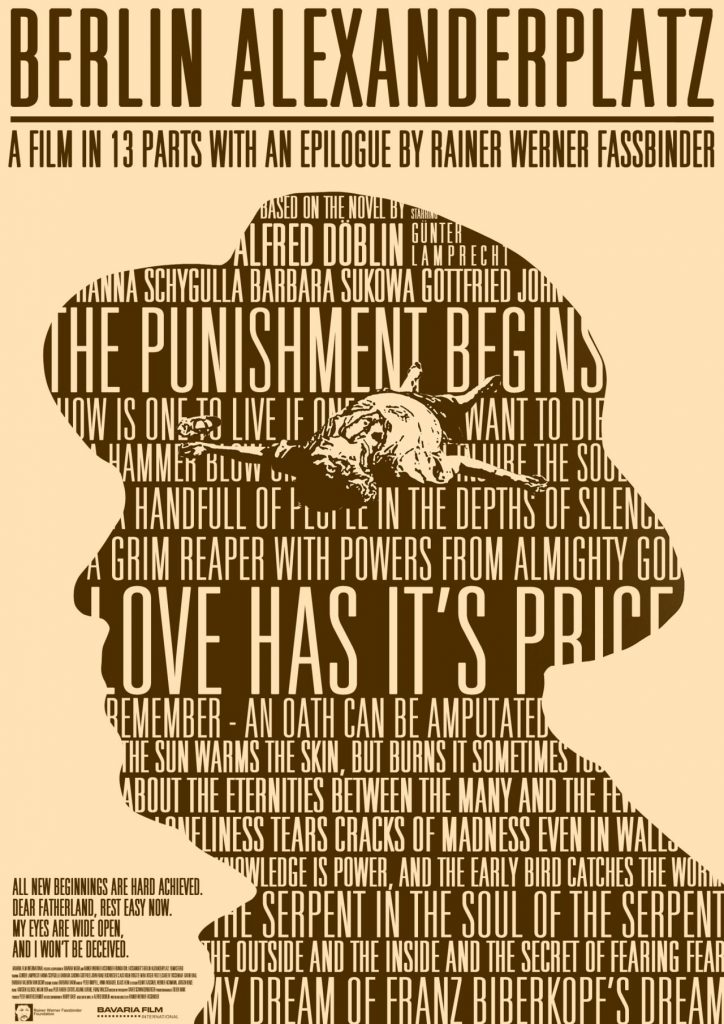

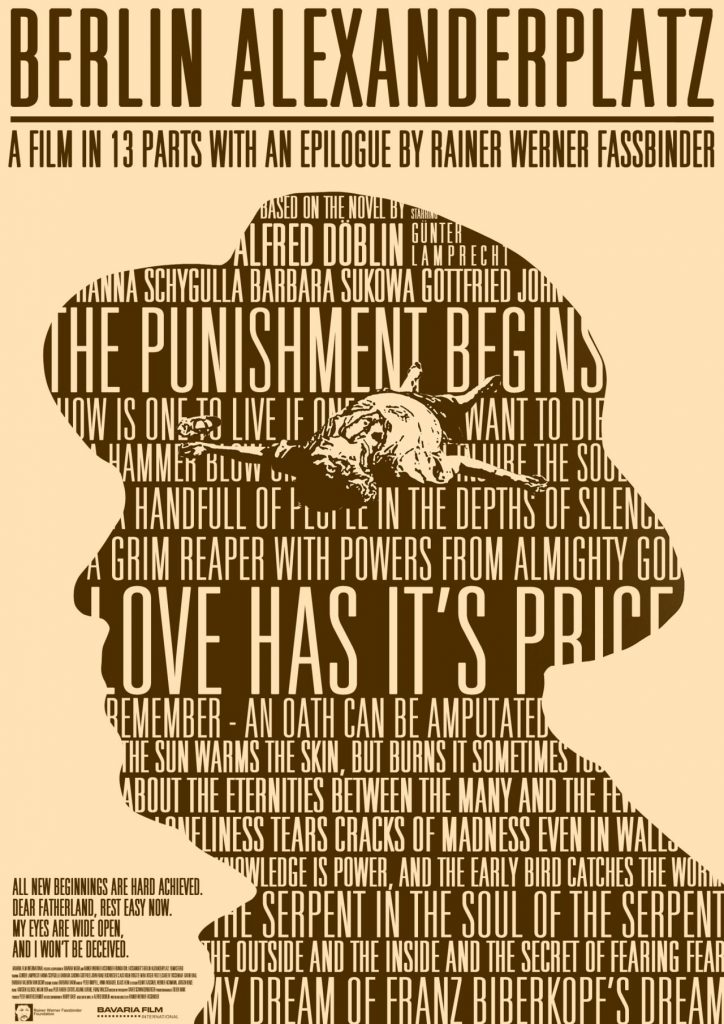

Juliane Lorenz was nineteen when she was hired to assist Ila von Hasperg (*) on Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Chinese Roulette. Beginning with Despair, she edited most of Fassbinder’s films thereafter, including Berlin Alexanderplatz, The Marriage of Maria Braun, Veronica Voss and Querelle, which she finished after his death. When she was twenty-four, she found him dead in their apartment (they were married). Lorenz then became the editor for Werner Schroeter (Malina, The Rose King), and since 1992, she has been head of The Fassbinder Foundation, producing and directing a feature documentary on him along with other projects.

Juliane Lorenz was nineteen when she was hired to assist Ila von Hasperg (*) on Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Chinese Roulette. Beginning with Despair, she edited most of Fassbinder’s films thereafter, including Berlin Alexanderplatz, The Marriage of Maria Braun, Veronica Voss and Querelle, which she finished after his death. When she was twenty-four, she found him dead in their apartment (they were married). Lorenz then became the editor for Werner Schroeter (Malina, The Rose King), and since 1992, she has been head of The Fassbinder Foundation, producing and directing a feature documentary on him along with other projects.

(*) Ila von Hasperg, it should be noted, also edited Fassbinder’s The Stationmaster’s Wife as well as Werner Schroeter’s The Death of Maria Malibran, Ulrike Ottinger’s Ticket of No Return, and Bette Gordon’s Variety, along with many other films.

“Rainer loved editors. He felt himself to be an editor. He used to say: ‘I do my job on the set and you do yours in the editing room. You are a second director. You have to finish the film, it’s

your responsibility.’ He inflamed me with that idea and that’s how I grew up.”

—Juliane Lorenz interviewed by Roger Crittenden in “Fine Cuts: The Art of European Film Editing.” The full interview can be found in the Appendix.

Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus

Born 1936

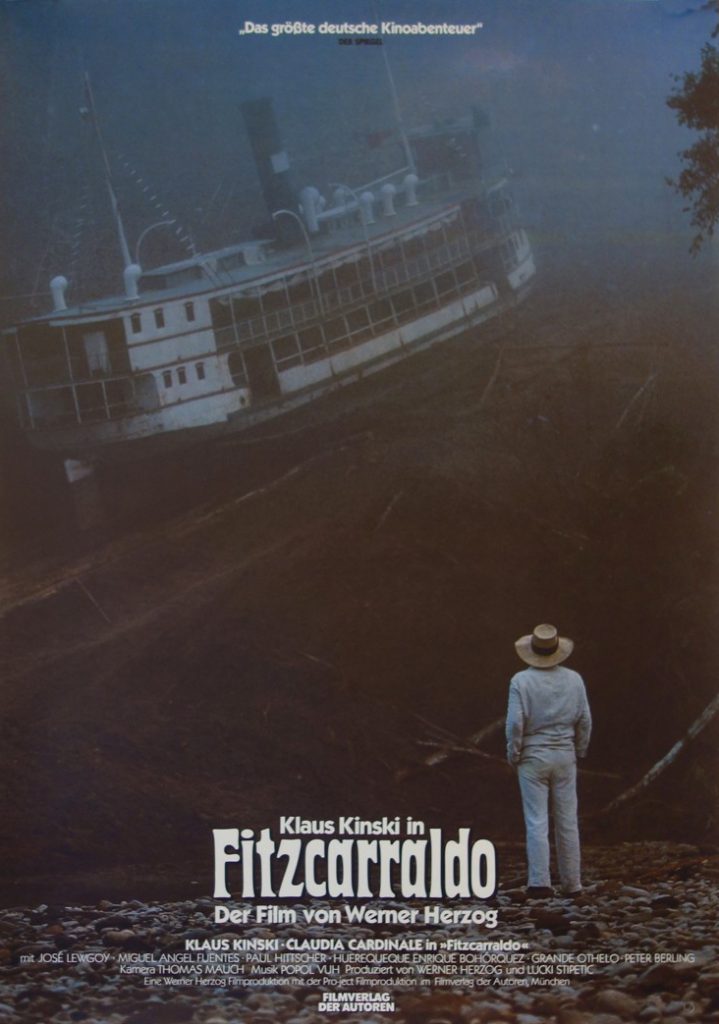

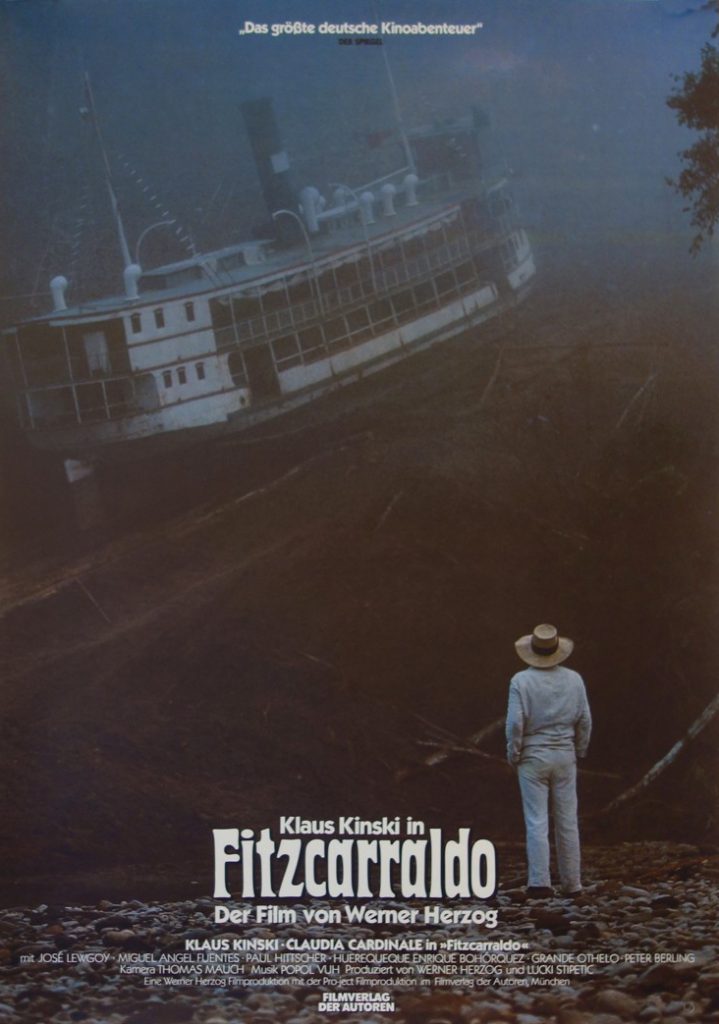

Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus was a member of the New German Cinema movement and has credits on more than twenty-five feature-length narratives and documentaries. Her work with Alexander Kluge includes Yesterday Girl and Artists Under the Big Top: Perplexed. Starting in 1968, she edited twenty films for Werner Herzog, including Stroszek, Heart of Glass, Fitzcarraldo, and Aguirre, the Wrath of God. In 1975, Mainka-Jellinghaus won the German Gold Film Ribbon for Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and for Kluge’s In Danger and Deep Distress, The Middleway Spells Certain Death.

Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus was a member of the New German Cinema movement and has credits on more than twenty-five feature-length narratives and documentaries. Her work with Alexander Kluge includes Yesterday Girl and Artists Under the Big Top: Perplexed. Starting in 1968, she edited twenty films for Werner Herzog, including Stroszek, Heart of Glass, Fitzcarraldo, and Aguirre, the Wrath of God. In 1975, Mainka-Jellinghaus won the German Gold Film Ribbon for Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and for Kluge’s In Danger and Deep Distress, The Middleway Spells Certain Death.

“I mostly look at the raw footage in fast forward, because otherwise it would take too long. What I am particularly interested in, I then watch slowly. Then I watch in high speed again and I sort the footage into small groups/blocks. If you do that (nonstop) for fourteen days, your head buzzes. Alexander Kluge and Werner Herzog said: Let her do it. When Alexander Kluge stood behind me, he said, “You need not say anything about your posture or how you operate the cutting table, I can already see where your interest lies.” Mostly he was surprised at the things that captivated or bored me. For the directors that is often very disappointing. They think everything is good and beautiful.”

“You have to be able to discuss, you have to be able to argue, you have to take the thing that you are working on seriously and you have to take the director seriously. That’s all part of it. You also have to like each other. If you do not like someone, you won’t last working so closely with one another. You have to internalize the theme that the other person presents to you, otherwise you cannot work together. When I come, I start at zero. The director has been dealing with it for much longer.”

—Two excerpts from “Schnitte in Raum und Zeit” by Gabriele Voss. The full text (in German) can be found in the appendix.

And finally: In 2022, Werner Herzog did a screening at Princeton University. During the Q&A afterward, he was asked about his long collaboration with Mainke-Jellinghaus. You can watch his very revealing answer here, which includes him saying, “From her I learned more than from anyone else in the film business.”

Juliane Lorenz was nineteen when she was hired to assist Ila von Hasperg (*) on Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Chinese Roulette. Beginning with Despair, she edited most of Fassbinder’s films thereafter, including Berlin Alexanderplatz, The Marriage of Maria Braun, Veronica Voss and Querelle, which she finished after his death. When she was twenty-four, she found him dead in their apartment (they were married). Lorenz then became the editor for Werner Schroeter (Malina, The Rose King), and since 1992, she has been head of The Fassbinder Foundation, producing and directing a feature documentary on him along with other projects.

Juliane Lorenz was nineteen when she was hired to assist Ila von Hasperg (*) on Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Chinese Roulette. Beginning with Despair, she edited most of Fassbinder’s films thereafter, including Berlin Alexanderplatz, The Marriage of Maria Braun, Veronica Voss and Querelle, which she finished after his death. When she was twenty-four, she found him dead in their apartment (they were married). Lorenz then became the editor for Werner Schroeter (Malina, The Rose King), and since 1992, she has been head of The Fassbinder Foundation, producing and directing a feature documentary on him along with other projects.

Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus was a member of the New German Cinema movement and has credits on more than twenty-five feature-length narratives and documentaries. Her work with Alexander Kluge includes Yesterday Girl and Artists Under the Big Top: Perplexed. Starting in 1968, she edited twenty films for Werner Herzog, including Stroszek, Heart of Glass, Fitzcarraldo, and Aguirre, the Wrath of God. In 1975, Mainka-Jellinghaus won the German Gold Film Ribbon for Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and for Kluge’s In Danger and Deep Distress, The Middleway Spells Certain Death.

Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus was a member of the New German Cinema movement and has credits on more than twenty-five feature-length narratives and documentaries. Her work with Alexander Kluge includes Yesterday Girl and Artists Under the Big Top: Perplexed. Starting in 1968, she edited twenty films for Werner Herzog, including Stroszek, Heart of Glass, Fitzcarraldo, and Aguirre, the Wrath of God. In 1975, Mainka-Jellinghaus won the German Gold Film Ribbon for Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and for Kluge’s In Danger and Deep Distress, The Middleway Spells Certain Death.